|

En esta entrada voy a comentar un error que una lectora de este blog sugirió en un comentario: cuidad por ciudad. Aunque no es uno de los errores más comunes, probablemente muchos maestros lo habrán encontrado en sus ensayos. De hecho, en el estudio de la Dra. Sara Beaudrie que ya mencioné anteriormente, se recoge este error, junto con otras inversiones de vocales, como teine por tiene, que incluso pueden cruzar el límite entre sílabas, como en gruadar por graduar. Creo que en estos errores entran en juego distintos factores, de los cuales voy a destacar estos dos: 1) Dificultades en la conciencia fonológica. La conciencia fonológica es la habilidad de identificar y segmentar los fonemas de una palabra. Esta habilidad se desarrolla en la infancia, mediante algunas actividades no escolares, como en canciones en las que se juegan con rimas (a, e, i, o u, burriquito como tú…), y más adelante en los primeros años de escolarización.  Esta es una habilidad necesaria para el desarrollo de la lecto-escritura, ya que la ortografía consiste en asignar letras a fonemas, pero, a su vez, el aprendizaje de la ortografía ayuda a identificar los fonemas de una palabra y a segmentar estas en cada una de sus unidades. Por ese motivo, nos parece que oímos mejor cada uno de los sonidos de una palabra cuando sabemos cómo se escribe. Hay estudios que sugieren que la conciencia fonológica es transferible, es decir, la conciencia fonológica que los estudiantes desarrollaron en inglés en sus clases de Kindergarten y primer grado se transfiere al español, con lo cual no tenemos que empezar de cero cuando los estudiantes toman su primera clase de español en la secundaria. Sin embargo, es muy posible que algunos estudiantes tengan algunas dificultades a nivel de conciencia fonológica en español, debido a que la conciencia fonológica tiene un efecto menor en la ortografía en inglés que el que tiene en español, y al hecho de que la conciencia fonológica desarrollada en la infancia disminuye con los años, cuando escribimos y leemos sin necesidad de fijarnos en cada letra. Las secuencias de vocales (ei, ie, iu, ou, …) son más difíciles de segmentar que las secuencias consonante-vocal (ma, te, po, li, ga). ¿Por qué? Porque la pronunciación de ciertas vocales es muy similar (e ≈ i, o ≈ u, i ≈ u, etc.) y al pronunciarlas consecutivamente las acercamos aún más, para facilitar la articulación (en un fenómeno llamado coarticulación), y porque las vocales en diptongo se pronuncian más rápidamente que las vocales entre consonantes. Por ese motivo, no es de extrañar que un estudiante con una conciencia fonológica no muy desarrollada en español tenga más dificultades en segmentar palabras con dos vocales consecutivas, lo cual da lugar a errores como cuidad (o suidad), teine, preferie o prefere, etc. En un estudio que realicé recientemente, esto es precisamente lo que observé. Los estudiantes tenían más dificultades con palabras que contenían vocales consecutivas en tareas como: escribir esas palabras a partir de un dictado, contar sus sílabas, y decir si habían oído una cierta sílaba (como pien) en una oración corta que habían escuchado. 2) Por otra parte, es muy posible que el error se deba a que el estudiante dicen "suidad", y que esa palabra forme parte de la variedad del español a la que está expuesto (o una de ellas). Por ejemplo, en el diccionario del español de Nuevo México y Colorado, de Rubén Cobos, se recogen palabras como: envitar, entriega, a escuras, espital for hospital, dijir, disierto, disconsuelo, dirigemos, dispensa, dispertar, nos divirtemos, divurcio, durmir, incontrar, imbicionar, empedido, empertinente, prencipal, prencipio, siñor, sirvir, sofrir y ... suidá (1). Y en una antología de cuentos en español de Colorado y Nuevo México, aparecen también palabras como envitado, rirse, incontrar, voltiar, pasiar, dicir, cairía, vían, nochi... y suidad (2). Si tenemos esto en cuenta, es muy posible que los estudiantes estén escribiendo ciertas palabras tal como las han oído y como las pronuncian. Mi sospecha es que la razón de muchos de los errores ortográficos que afectan a las vocales se encuentra en una confluencia de estos dos factores. Cobos, Rubén (2003) “A Dictionary of New Mexico and Southern Colorado Spanish” 2nd edition. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press. Rael, J.B. (1939). Cuentos Españoles de Colorado y de Nuevo Méjico (Primera Serie).The Journal of American Folklore, 52, 205/206, 227-323.

3 Comments

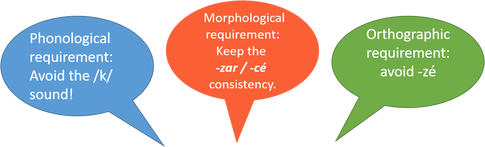

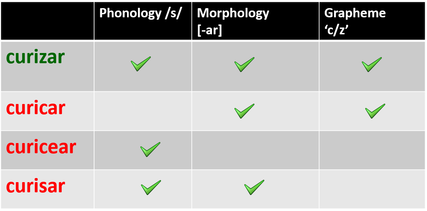

I am a strong believer that in order to help students to correct or avoid spelling errors, we need to understand why they make that particular error. It is not enough to say: “they should have written ‘c’ instead of ‘s’.” We need to understand why the student wrote ‘s’ instead of ‘c’ in that particular context. And, for that, we need to consider why we need to write ‘c’ and reject all the other options. In this post, I want to focus on one particular error. In a previous post, I explained that many spelling errors involving s/z/c were found in verbs ending in –zar, such as empezar, empecé, empezó, alcanzar, alcancé, alcanzamos, etc. And here I want to explain why these words are particularly problematic, as well as a little experiment that I did, and that you can do in your classroom. First, these words are particularly problematic because the sound /s/ is associated with three different letters: s, z, and c. Therefore, the student needs to choose between three options. Second, the different choices require different strategies. Let’s see… To write empezar, we need to write z and reject ... s (*empesar), because that’s how the word is spelled. There is no orthographic rule that allows us to know that. In fact, other verbs end with -sar: like pesar, pensar, besar, or pasar. That makes the word *empesar not so ugly at our eyes (or the students' eyes). c (*empecar), because that would result in the wrong pronunciation: like /empekar/. Now, to write empecé, we need to write c and reject ... s (empesé), because empecé is a conjugated form of of empezar, and not empesar. Z (empezé), because there is a rule that says that z appears only at the end of a word or before a, o, u, but not before e or i. Therefore, the reason why writing verbs ending in –zar is so difficult is that the student faces three conflicting requirements: In 2017, I conducted an experiment with Spanish HL students.* I gave them sentences with made up words similar to empezar, which they had to complete with a related made-up word. Try to complete the sentence before you look at the right answer. Ayer yo curicé mi pasaporte, pero tú todavía lo tienes que ______________. [scroll down to see the answer] The right answer is curizar. Did you come up with this word? A few students did, but many of them wrote the wrong word. What was interesting is that their wrong answers were either: curicar curicear curisar Each of these words is the result of breaking one of the demands for that word, as shown in this table. What does that experiment show us?

It shows us that writing verbs like alcanzar, empezar, … and their related forms is much more difficult that it might seem, because writing the right form requires paying attention to different (and conflicting) things. Most of us can do it because we have a strong visual memory of these written words. Doing this experiment with made-up words allows us to look at those words without having any visual memory of them. You can try this experiment with your students, as a spelling game, with the objective of forcing students to focus their attention to the morphological relations between words and the –zar > -cé alternation. Here are some sentences you could use:

*Llombart-Huesca, A. (2017). “Morphological Awareness and Heritage Language Learners.” Linguistics and Education, 37, 11-31. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.  Cuando alguien tiene errores ortográficos, inmediatamente piensa que necesita “aprender las reglas”. Sin embargo, el aprendizaje de las reglas ortográficas tiene un efecto limitado, por varias razones:

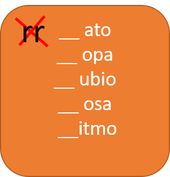

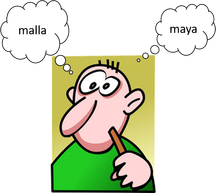

La mayoría de los errores ortográficos (aunque no todos) se producen cuando existe más de una letra para representar un mismo sonido. Es el caso, por ejemplo, de las letras ‘s’, ‘c’ y ‘z’ para representar el sonido /s/, o las letras ‘b’ y ‘v’ para representar el sonido /b/. Al representar estos sonidos, el escritor tiene que elegir entre una letra u otra, y el error se produce al elegir la que no le corresponde. ¿Cómo tomar esa decisión? En algunos casos, existen reglas ortográficas (o reglas contextuales): tomamos la decisión mirando las letras que se encuentran al lado de la letra que tenemos que escribir. Pero en otros casos, no existe ninguna regla ortográfica (contextual). Y ser conscientes de esa diferencia es muy importante, tanto para el maestro como para el estudiante. Por ejemplo, para decidir entre ‘r’ y ‘rr’ para representar el sonido de la ‘r’ múltiple, existe una regla ortográfica: Escribimos ‘r’ al principio de palabra y después de consonante; y escribimos ‘rr’ después de vocal. Sin embargo, para decidir si escribimos ‘y’ o ‘ll’ (suponiendo que en nuestra variedad del español las dos se pronuncien igual), no tenemos ninguna regla en sí. Pollo se escribe con ‘ll’ y mayo se escribe con ‘y’… porque sí. (No realmente “porque sí”; pero el motivo no resulta útil al estudiante que está tratando de decidir qué letra escribir). ¿Por qué es importante distinguir entre estos dos tipos de decisiones? Porque en el primer caso, hay una regla que aprender. Al aprender esa regla, podemos escribir incluso palabras que no hemos visto escritas antes, o que incluso estamos oyendo por primera vez. Por ejemplo, si tenemos que escribir rubio, alrededor o perro, no necesitamos haber visto esas palabras antes, ya que con seguir la regla acertaremos al escribirlas. Sin embargo, si tenemos que escribir palabras como pollo, mayo, callar, rallar o rayar, necesitamos saber qué letra (y o ll) llevan, ya que no hay nada que nos lo pueda indicar.

Despite the fact that Spanish Heritage Language Learners (SHLs) have many difficulties with spelling, the development of spelling proficiency has not received much attention in HL research, so far. One exception to this is Dr. Sara Beaudrie, a professor of Spanish Linguistics at Arizona State University, where she also serves as the coordinator of the Spanish heritage program. In 2012, she published a description of the most common orthographic errors of HLs, based on writing samples obtained from 100 college students. Beaudrie found that the great majority of misspellings involving consonants were the result of overusing the letter ‘s’, which was used in place of either ‘c’ or ‘z’, as in hise, vacasiones, tristesa and empesar. Less common, but still very frequent, were the opposite cases, that is, the use of c and z instead of s, as in demaciado and riza. Other errors in the spelling of consonants involved h, b/v, r/rr, j/g, and y/ll. None of these errors will surprise the SHL instructor, who is probably seeing them constantly in their students’ work. However, one of the most important contributions of Sara Beaudrie’s study is that it identifies the words and word types where the bulk of spelling errors fall: 1. More than half of the errors consisting in the overuse of ‘s’ were found in these groups:

2. Almost all ‘h’ misspellings (91%) were found in only six words (and their variations):

Source: Beaudrie, S. (2012). A corpus-based study on the misspellings of Spanish heritage learners and their implications for teaching. Linguistics and Education, 23, 135-44. |

BLOG ON SPELLING

This is a blog about spelling in Spanish Heritage Language Learners. Some posts will be in Spanish and some in English. Feel free to ask your questions in the comments section.

Archives

September 2023

Popular Posts

Made-up words and other fipers. Tips for teaching stress marks. Los hablantes nativos y la ortografía |