Are you thinking I am going to talk about the way students "make up words" with their spellings? Well, I am not. First, because I do not believe students make up words when they make spelling errors, but they are really trying to spell real ones. What I want to talk about is made-up words that are made up... by teachers, known as pseudo-words. Pseudo-words are made-up words that look like real words in a certain language. Pseudo-words in English could be brike, loke, fiper, or dight. They do not exist as words in English, but they are pronounceable and follow patterns found in real English words, such as bride, poke, fiber, and light. Pseudo-words like blaya, rila, pacar, or puelo are nonexistent but possible words in Spanish (similar to playa, pila, rima, picar, and suelo). Pseudo-words have a space in the language classroom. Let’s see one example today. Let’s say you want students to learn the writing of the GUE, GUI sequences, vs. the writing of GE, GI. If you only use examples like “guerra” and “gente,” it is very likely students will read and spell those words right, giving the impression that they are perfectly aware of the contrast ge/gue. However, they will read and write them right because they already know those words. When students read them, they do not need to pay attention to the exact sequence of letters, because they simply recognize the words. And when students write them, they will probably spell them right because they have seen them before. However, when they need to write less familiar words, they will make errors like llege, lleguo, … If we want students to pay attention to the orthographic contrast (GE - GUE) so that this orthographic sequence is applied to ALL words (familiar, infrequent, and new words), you can use pseudo-words. For example, students can be asked to read these words: guelo - laguifa - gipar – lugueto – piguenar – pegifante – pogé Because students have never heard those words before, they cannot use the “recognition strategy,” that is, recognize the word and just say it as they know it is pronounced. They really need to pay attention to that orthographic pattern. You can also use these pseudo-words in dictation: you read them and students write them. I would add two more benefits of using pseudo-words in the class, in addition to the main benefit of directing students' attention to the specific orthographic aspect: 1) It is fun! Working with made-up words adds a playful element to the lesson. 2) It helps lessen the fear to unknown words. The presence of an unknown word in a sentence creates an uncomfortable feeling to some students, which makes them sort of freeze and not be able to understand anything else in the sentence. The first time I work with pseudo-words in a classroom, some students laugh nervously. But working with these made-up words helps those students to get used to encountering unknown words. (With the idea that when those unknown words are real, their lack of fear will allow them to work on context clues and vocabulary-increasing activities). Now, although the use of pseudo-words has its benefits in the classroom, it should be limited, and applied only on specific occasions with a specific purpose. A very important component of spelling is visual memory. After reading and writing a word many times, for years, that word gets engraved in our memory, and we do not need to think about the rules to write it. Therefore, students should spend most of their time writing real words, which are the ones that should get engraved in the students’ mental visual dictionary. Likewise, there is nothing wrong with reading using a “recognition strategy”. This is what allows us to read fast and fluently, and to focus on comprehension of texts. Therefore, teachers should focus on increasing students’ vocabulary, through reading and talking about a variety of topics in a variety of genres, registers, and styles. In future posts I will give other ideas for using pseudo-words in the classroom… in a timely manner. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.

0 Comments

There is no way to avoid the issue of the stress marks (acentos) when talking about spelling in courses of Spanish for Heritage Language Learners. Many students and teachers will agree that this is one of the most difficult aspects of spelling to learn. And it is! In order to place the stress mark in the right place, the writer needs to:

And ... do all this in the back of your head while you think of more important things, such as the ideas you want to express. And do so very quickly, because you need to move on to the next word. However, as many students, teachers, and researchers have noticed, the process stops at the second step, when students cannot identify the stressed syllable of the word. Dr. María Carreira, a professor of Spanish Linguistics at Cal State University Long Beach, explained that the problem is not that the students lack the ability to perceive stress, but rather that they seem unable to access this implicit perception and turn it into an explicit identification. It makes sense. If the student didn't know (implicitly) what the stressed syllable was, they would not pronounce the word right. And that's not the case. Dr. Carreira trained the students into improving their ability to locate the stressed syllable of a word, by making them listen recordings of words in which the stressed syllable was read with an amplified pitch, length, and loudness. Dr. Sara Beaudrie, another professor and researcher I have mentioned before in this blog, also conducted a study in which she trained students to identify the syllable before the rules where introduced. I want to suggest here an alternative (or, rather, complementary) manner to address stress marks in the classroom: study groups of words that are related and that follow the same pattern. For example, the past tense (preterit) for yo and él / ella: such as: nací, crecí, vivió, nació, creció, vivió, empezó, estudió, etc. (Regular verbs only). Students, by themselves or in groups, can write autobiographies or someone else’s biography, and work with those forms. Other groups of words that share a stress pattern while sharing some communicative functions are:

Working on each of these groups has the following benefits:

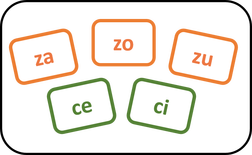

That said, identifying the stressed syllable, learning the rules, and even grouping words into patterns, will not be enough. Adding the stress mark to a word has to become automatized enough so that the student can do it while focusing on something else. As with many other aspects of language, we need to distinguish between competence and performance. While a student might know where and where to write the accents (competence), they might not do it every time they write something (performance). As tempting as it might be to repeat the rules over and over, students should be given the opportunity to practice placing the stress marks so that it becomes an automatic task that does not require any thinking. References: Beaudrie, S (2017). The Teaching and Learning of Spelling in the Spanish Heritage Language Classroom: Mastering Written Accent Marks. Hispania, 100, 4. Carreira, M. (2002). When phonological limitations compromise literacy: A connectionist approach to enhancing the phonological competence of heritage language speakers of Spanish. In S. Hammadou (Ed.), Literacy and the second language learner. Greenwich, CT: IAP. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.  In a previous post, I mentioned that spelling rules have a limited role in the development of spelling. One of the reasons for that limited role is the fact that our mind does not have the time to stop and recall a specific rule during real time writing. Instead, our mind relies more strongly in the visual memory of the word. After repeated exposure to a written word, as well as after repeatedly writing that word for years, the visual image of that written word is engraved in our mind. This allows us to read and write more quickly and confidently. And it’s that stored image of a word that allows us to reject a misspelled word with a feeling that “it looks bad”.  However, students keep asking for rules … and then forgetting them. There is nothing wrong with forgetting a rule, but only if the image of that word is strongly engraved in the mind so that the rule is not really needed. In a workshop for prospective teachers (heritage language themselves), I asked the students: “Why do you think spelling is so difficult?” And a few responded: “Because students are lazy and don’t study the rules”. Then, I proceeded to explain a very simple spelling rule: when you have to choose between Z and C, Z is used before A, O, U; and C is used before E and I. And I gave a few examples. Students told me they understood the rule--and most of them were familiar with it already. Immediately after that, I gave them a dictation of words, and I told them that none of them were spelled with S, only Z or C. Among those words were: cine, cena, zapato, cereza, hice, realicé and cero. Can you guess which ones many of them got wrong? Yes, they were realicé and cero. More than half of the class wrote zero, and more than one third wrote realizé. There were no errors in any of the other words, despite the fact that they followed the same rule. Students were obviously swayed by the visual image of zero and realize in English. When I showed students why those spellings were wrong, according to that simple rule they had just learned, a few still “complained” that cero and realicé looked wrong. Students were not lazy, or forgetful; the memory of the image of zero and realize simply had a greater weight. This is not so strange. When we see a friend on the street, we recognize his or her face because we have a stored memory of it, not because we “know” some facts about that friend’s face. When we see a red light it just feels right to stop; we do not need to think about the rule: green > go; red > stop. For cases in which the spelling of a word goes against a strong image of a word, students will need negative instruction (that is, what NOT to write) and many opportunities to strongly engrave the image of that word in their minds. Here are some other words similar to cero and realicé: analicé, docena, cebra, bronce, utilicé, trapecio. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment. |

BLOG ON SPELLING

This is a blog about spelling in Spanish Heritage Language Learners. Some posts will be in Spanish and some in English. Feel free to ask your questions in the comments section.

Archives

September 2023

Popular Posts

Made-up words and other fipers. Tips for teaching stress marks. Los hablantes nativos y la ortografía |