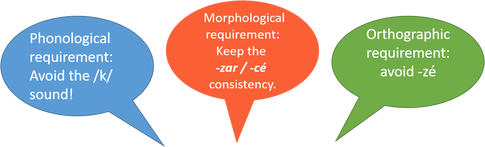

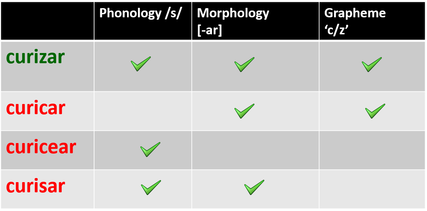

I am a strong believer that in order to help students to correct or avoid spelling errors, we need to understand why they make that particular error. It is not enough to say: “they should have written ‘c’ instead of ‘s’.” We need to understand why the student wrote ‘s’ instead of ‘c’ in that particular context. And, for that, we need to consider why we need to write ‘c’ and reject all the other options. In this post, I want to focus on one particular error. In a previous post, I explained that many spelling errors involving s/z/c were found in verbs ending in –zar, such as empezar, empecé, empezó, alcanzar, alcancé, alcanzamos, etc. And here I want to explain why these words are particularly problematic, as well as a little experiment that I did, and that you can do in your classroom. First, these words are particularly problematic because the sound /s/ is associated with three different letters: s, z, and c. Therefore, the student needs to choose between three options. Second, the different choices require different strategies. Let’s see… To write empezar, we need to write z and reject ... s (*empesar), because that’s how the word is spelled. There is no orthographic rule that allows us to know that. In fact, other verbs end with -sar: like pesar, pensar, besar, or pasar. That makes the word *empesar not so ugly at our eyes (or the students' eyes). c (*empecar), because that would result in the wrong pronunciation: like /empekar/. Now, to write empecé, we need to write c and reject ... s (empesé), because empecé is a conjugated form of of empezar, and not empesar. Z (empezé), because there is a rule that says that z appears only at the end of a word or before a, o, u, but not before e or i. Therefore, the reason why writing verbs ending in –zar is so difficult is that the student faces three conflicting requirements: In 2017, I conducted an experiment with Spanish HL students.* I gave them sentences with made up words similar to empezar, which they had to complete with a related made-up word. Try to complete the sentence before you look at the right answer. Ayer yo curicé mi pasaporte, pero tú todavía lo tienes que ______________. [scroll down to see the answer] The right answer is curizar. Did you come up with this word? A few students did, but many of them wrote the wrong word. What was interesting is that their wrong answers were either: curicar curicear curisar Each of these words is the result of breaking one of the demands for that word, as shown in this table. What does that experiment show us?

It shows us that writing verbs like alcanzar, empezar, … and their related forms is much more difficult that it might seem, because writing the right form requires paying attention to different (and conflicting) things. Most of us can do it because we have a strong visual memory of these written words. Doing this experiment with made-up words allows us to look at those words without having any visual memory of them. You can try this experiment with your students, as a spelling game, with the objective of forcing students to focus their attention to the morphological relations between words and the –zar > -cé alternation. Here are some sentences you could use:

*Llombart-Huesca, A. (2017). “Morphological Awareness and Heritage Language Learners.” Linguistics and Education, 37, 11-31. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.

7 Comments

Stella Manley

1/23/2018 10:51:40 am

How would you explain the recurrent error of spelling CUIDAD instead of CIUDAD? Gracias!

Reply

Amalia

1/23/2018 11:56:50 am

Gracias por tu comentario / pregunta. Voy a escribir mi próxima entrada sobre esa palabra (y otras similares).

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG ON SPELLING

This is a blog about spelling in Spanish Heritage Language Learners. Some posts will be in Spanish and some in English. Feel free to ask your questions in the comments section.

Archives

September 2023

Popular Posts

Made-up words and other fipers. Tips for teaching stress marks. Los hablantes nativos y la ortografía |