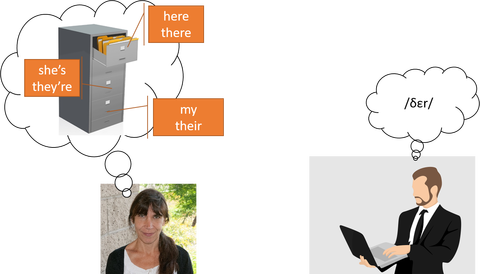

Algunos instructores se sorprenden de que los estudiantes no-nativos cometen menos errores ortográficos que los estudiantes que son hablantes nativos. Algunos estudiantes de español como lengua de herencia también se avergüenzan al ver que cometen más errores de ortografía que sus compañeros no nativos. Sin embargo, no hay nada extraño en esto ni nada de qué avergonzarse. Las dificultades con la ortografía de una lengua son propias de los hablantes nativos de esa lengua. Por definición, un hablante nativo pasa años hablando su lengua antes de empezarla a escribir—típicamente, a la edad de entre 4 a 6 años. Antes de ese momento, el niño ha pasado años diciendo y oyendo las palabras hizo, a veces, empecé, voy a hablar... en contexto, sin prestar atención a esas palabras. Para ser más exactos, ha pasado años usando diciendo y oyendo [íso], [aβéses], [empesé], [bojaβláɾ], etc. Y, si queremos ser más exactos, en realidad, ha pasado años diciendo y oyendo esas tiras fónicas en el interior de otras mayores, como en [kjenísoesto]. Durante años, estas palabras estuvieron almacenadas en su mente sin ninguna forma escrita asociada a ellas. Al entrar en la escuela, el niño aprende a segmentar esas secuencias fónicas en sonidos individuales y a representarlos por unos símbolos: las letras. Durante el proceso de alfabetización, el niño se familiariza con secuencias de letras escritas. Pero el sonido vino antes, y eso tiene mucho peso en la forma en la que el niño concibe las palabras. En contraposición, el estudiante de español como lengua extranjera pasó de no conocer una palabra, por ejemplo, hacer, a aprender a la vez el sonido, la escritura y el significado de esa palabra. Y el mismo día que aprendió la palabra hacer, aprendió a conjugarla, es decir, a escribir yo hago, tú haces, él hace, nosotros hacemos, etc. Para esa persona, hacer sin “h” ni siquiera es una opción. Esa palabra está guardada en su mente con esa escritura. Lo mismo sucede al aprender otras lenguas. Por ejemplo, un error común entre hablantes nativos de inglés es confundir la escritura de “their”, “there”, “they’re”. Este error se debe a que las tres expresiones se pronuncian igual. Cuando el niño anglohablante aprende a escribir, ya lleva años usando esas palabras, sin haberse detenido a pensar en lo que significan, es decir, si es un posesivo, si es una contracción de “they + are”, etc. Sin embargo, un estudiante no anglohablante que está estudiando inglés en una escuela de su país, un día estudia los pronombres posesivos y aprende a decir y a escribir my, your, his, her, their. Otro día estudia el verbo to be y aprende I am > I’m; you are > you’re; they are >they’re. Y otro día estudia los adverbios de lugar y aprende here y there. De este modo, their, they’re y there están guardadas en tres lugares diferentes de la mente, y el estudiante de inglés como lengua extranjera raramente las confunde. De hecho, no fue hasta que leí que la escritura de there-they’re-their era una causa común de confusión, que me di cuenta de que sonaban igual. En mi mente, esas tres expresiones estaban guardadas en su forma escrita en diferentes lugares. En conclusión, la ortografía causa más dificultad a los hablantes nativos que a los no-nativos, y por ese motivo, no es de extrañar que encontremos más errores ortográficos en los escritos de los estudiantes de español como lengua de herencia.

0 Comments

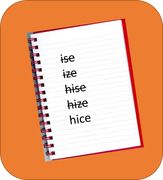

If you teach a Spanish for Spanish Speakers course (or Spanish for heritage speakers, Spanish for Native speakers) you are probably aware that students make many spelling mistakes. Not only that; spelling mistakes seem to be very persistent. No matter how many times we correct them, students keep making the same mistakes. This may cause some frustration in teachers, who keep attempting different methods for addressing these errors. I want to suggest instructors do something that will not only help (eventually) improve the students’ spelling mistakes, but will also make the task most enjoyable for the instructor: Enjoy and appreciate spelling errors. Conducting research on SHLs’ spelling has made me look at spelling errors differently. In my research, I look at a particular set of errors, errors I think follow a pattern, and I think of ways to find out what is behind that error. But you don’t need to engage in formal research in order to look at misspells in a different way. If you have a classroom, you have a wonderful set of interesting data to enjoy, appreciate, and learn from. For example, if you hear yourself saying things like: "Why do they write hací instead of así???" or "Why do they keep writing aveses?" or "Why can’t they see it’s a ver and not haber?" Then, make that question a real one. Look at an error that surprises you, an error that doesn’t seem to have any explanation. For example, hací instead of así. And think about the reason why the student wrote it this way: Is it because we have insisted on the spelling of hacer, and they are writing hací by analogy to hacer and its forms (hice, hacía, etc.)? Or maybe it’s because así seems “too easy” or “too simple,” and they remember a time when they wrote a word the way it seemed easier (as when they wrote “ise” instead of “hice”) and they got it wrong. Maybe you won’t know for sure the reason why they made that spelling error, but looking at it with real curiosity and feeling really intrigued about it will make dealing with spelling errors much more enjoyable. |

BLOG ON SPELLING

This is a blog about spelling in Spanish Heritage Language Learners. Some posts will be in Spanish and some in English. Feel free to ask your questions in the comments section.

Archives

September 2023

Popular Posts

Made-up words and other fipers. Tips for teaching stress marks. Los hablantes nativos y la ortografía |