|

A lot has happened since the last time I posted. But I was not away from my research and workshops on spelling. And now I am happy to announce that my book Spelling in Spanish Heritage Language Education, Georgetown UP is coming out next spring.

I cannot write here the names of all the people I am thankful for, but, for sure, if you are reading this blog, you are one of them.

0 Comments

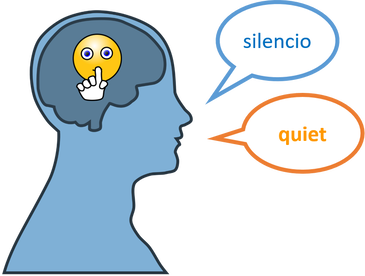

Some spelling errors that might stun teachers are words like *acecino, *silensio, *comunicion, … While the fact that they write s instead of c (and vice versa) is easy to understand—since these two letters sound the same—what can be surprising is that they do it with words that are very similar in English? If a student can write silence, why do they write silensio, and not silencio, with the same consonants? Also surprising can be the shortening of long words, since for a teacher the connection between the English word and the Spanish counterpart is so obvious: com – mu – ni – ca - tion co – mu – ni – ca – ción Of course, there are some differences, but the syllables are basically the same. However, the connection between the two languages is not always made by simultaneous bilinguals. In addition, the connections that are made are more holistic and based on meaning, not form. It is not that they do not know that silence translate as silencio, but this connection is not present when writing. This would not be an unlikely scenario: Teacher: - Silencio, por favor. Student 1: - What did she say? Student 2: - She told us to be quiet. A student who wants to write asesino might have the word murderer closer to it in mind than assassin. (In fact, the words asesino and assassin, while having the same Arabic origin, they have different uses in the present). In fact, this is just an example of the natural connection that speakers have of their language. At first, we see language for their meaning and communication power. We do not pay attention to formal properties. School literacy activities, while strengthening the ability to create meaning, also shift the students’ attention to the formal aspects (how words are written, grammar, etc.). For students who grow up bilingual, the same applies to both languages and the connections between them. That might surprise learners of Spanish or English as a second language. When we learned that second language as adults / young adults, we made connections with the first language we spoke. English speakers who learn the word “simpático” in Spanish might connect it with the now English word “simpatico” (even tough is not as common as “nice”). Spanish speakers who see “assassin” will relate it to “asesino.” In fact, some focus on Second/Foreign language classes is to notice the difference in meaning between cognate pairs, since a second/foreign language learner might assume that if they look similar, they mean exactly the same. One activity that I do in the Spanish for Heritage Speakers classroom to strengthen the connection between Spanish-English words, so that students can benefit from the spelling similarities, is to ask students to find a similar word—even if the meaning is slightly different. These are some of these words: From Spanish to English: asesino silencio mansión artificial cerebral explosión horizontal grave edificio From English to Spanish: religious insect adherence palace ceramics television alcohol grace hospital It is obvious that English grave and Spanish grave are not exactly the same; and that the word edifice is not very common; however, the goal of this activity is not to work on meaning but on formal properties. The ultimate goal is to use students’ knowledge of English spelling to facilitate Spanish spelling.  El pasado 21 de abril presenté un taller sobre la enseñanza de la ortografía en las clases de español como lengua de herencia. ¡Gracias a todos los asistentes por su interés, participación y sugerencias! Nuestro próximo congreso será en UC Santa Bárbara el 27 de octubre de 2018. Espero que puedan asistir. En la entrada del blog de hoy, pueden encontrar la versión PDF de la presentación en power point que utilicé en el taller, así como el "handout" con el que presenté algunas ideas para preparar actividades de ortografía.

***********************

Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) in your classes you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.  Today I want to talk about a situation I have witnessed with my students, which I am sure many teachers have too. On occasions, a student is reading a paragraph aloud, with apparent fluency and accuracy, when suddenly they will stumble over one word. And that word does not even have to be the longest in the text! Why does that happen? If you ask the student if they know the word they stumbled with, they probably say they don’t. In fact, that often happens with names of people or places they are not familiar with. If a student can read long words they are familiar with but then they stumble over an unknown word, then the problem is with their decoding skills. We have two main ways to read a word:

However, when we encounter a new word, we cannot identify it, and we quickly switch to our decoding mode, to be able to read it. Next time we encounter that word, we probably won’t need to do that again, since we will be able to identify it. So, if a student can read known words but have difficulties reading an unknown word, what happens is that the student has difficulties decoding each letter into a sound. Many Spanish heritage language learners did not develop their decoding skills to their fullest, in part because these skills are not as necessary in English. That doesn’t mean they don’t know the alphabet in Spanish. Probably, the student is not used to switching to the decoding mode of reading, but some practice will refresh and strengthen those skills. The best way to practice decoding skills is with unknown words, of course. You can create made-up words o give them words that you know they don’t know, and ask them to read them. The goal is not to memorize them, but to decode them. For this practice, once they successfully read the word, there is no need to go over it. After that, they would not be “reading” (decoding) the word, they would be “saying” it. Using names of not well-known cities can be a good idea: becoming familiar with those names might be useful (more useful than learning a made-up word) but we are not burdening the student with also learning the meaning of the new word. Of course, learning new words with their meaning is important, but for this practice, the goal is being able to easily go over each letter and saying that word, so that when they encounter a new word in their reading, they can read it successfully. Happy decoding! Decode this! Click here to hear parangaricutirimicuaro. Click here to hear Mary Poppins in Spanish. Click here to hear another interesting word. ***********************

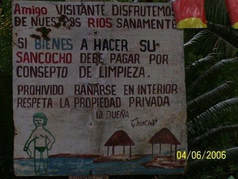

Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.  El otro día encontré por casualidad un video hecho con la intención de ayudar a mejorar la ortografía y la escritura en español, y algunas cosas que vi y oí me molestaron un poco. En la entrada de hoy voy a comentar algunas de las ideas que oí en ese video. No es solo porque no esté de acuerdo con lo que decía la autora; lo que me lleva a querer comentar algunas de las cosas que decía es que reconocí las ideas y la actitud que mucha gente tiene sobre la ortografía. Ideas y actitudes que no ayudan a nadie. No voy a poner un enlace aquí porque no quiero entrar en el juego del "cyber-bullying", y menos cuando lo que quiero criticar es la actitud del "orthographic bullying". Estas son algunas de las frases que decía la autora en su video (parafraseo): “En nuestra vida cotidiana encontramos errores y horrores de ortografía que a veces nos producen risa y otras, vergüenza” ¿Qué problema veo con esto? Primero, la palabra “horrores”. El juego de palabras (errores - horrores) puede tener su chiste, e incluso es posible que yo lo haya usado alguna vez y me haya creído muy astuta. Pero no creo que haga ningún bien a nadie. Los “horrores” son malos, por definición; los errores, no. Los errores son parte del aprendizaje, y usarlos para entender en qué punto del desarrollo se encuentra el estudiante es una de las labores claves del maestro. Los errores reflejan la forma en que el lenguaje está representado en la mente. El maestro necesita observarlos bien y entenderlos para saber cuál es va a ser la mejor estrategia a seguir. Por ese motivo, los errores son muy interesantes. Un maestro no puede enfrentarse a los errores pensando que son aberraciones. Por otra parte, … ¿vergüenza y risa? Un maestro nunca debe reírse de sus estudiantes. Y un estudiante nunca debe sentirse avergonzado de sus errores y de la etapa de aprendizaje en la que se encuentra. Para ser justos, la autora del video no estaba hablando de los ensayos de sus estudiantes, sino de cosas escritas en paredes, carteles, redes sociales,... Pero esa actitud tampoco me parece justificada. Primero, ¿qué sabemos nosotros de las circunstancias de esa persona, de las oportunidades que ha tenido para aprender ortografía? ¿Y quiénes creemos nosotros que somos para sentir vergüenza por otras personas o reírnos de ellas? Y, segundo, si consideramos los errores ortográficos de otras personas como horrores que inspiran risa o vergüenza, nos va a resultar difícil cambiar totalmente nuestra actitud cuando vemos el trabajo de nuestros estudiantes. Muchos de los errores cotidianos tienen que ver con el desconocimiento de las normas, la falta de lectura, o porque las redes sociales y las conversaciones por chat nos han acostumbrado a ser perezosos y nos han ensenado que debemos escribir con horrores y no pasa nada. Por partes: Muchos de los errores cotidianos tienen que ver con el desconocimiento de las normas Esto es una sobresimplificación. Como he comentado en algunos posts, la ortografía es mucho más que la aplicación de unas normas. De hecho, el conocimiento de las reglas tiene un impacto bastante menor en la ortografía, comparado con otros aspectos (como la memoria visual o la conciencia morfológica). la falta de lectura Es cierto que la lectura tiene un efecto positivo en la ortografía (entre otras cosas). Pero, 1) ese efecto en la ortografía es limitado los adultos y 2) no todos hemos tenido el mismo acceso a la lectura cuando éramos niños. Tal vez deberíamos evitar esa actitud de superioridad moral de los lectores ávidos sobre los que leen menos. Sí, promovamos la lectura, llevemos a cabo iniciativas que promuevan la lectura y el acceso a los libros y a las bibliotecas, pero dejemos de menospreciar a los que no desarrollaron esa pasión por la lectura. La falta de acceso a libros en la niñez provoca dificultades en la lectura que hacen que esta sea menos placentera. O porque las redes sociales y las conversaciones por chat nos han acostumbrado a ser perezosos Pereza, otro pecado que nos hace sentir moralmente superiores a otros. Pero detrás de escribir con abreviaciones, sin mayúsculas, etc. en los mensajes de texto no hay tanto pereza como el darle prioridad a la rapidez. Y nos han ensenado que debemos escribir con horrores y no pasa nada. Y es que es posible que no pase nada. Y tampoco creo que nadie crea que “debamos” escribir con errores. Si uno quiere escribir con todas las letras, no creo que haya nadie que se lo prohíba. De hecho, con los teléfonos actuales y la función de autocorrección, es difícil escribir con abreviaciones, sin mayúsculas o con faltas de ortografía. Y cuando se escribe así, lo peor es que esto se lleva también a la escritura académica. No es cierto. No necesariamente. Escribir mensajes de texto es una actividad totalmente distinta a la de escribir académicamente. Decía el profesor José Portolés Lázaro, catedrático de Lengua Española de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, que nadie obtiene la licencia de manejar por montar en bicicleta. Y añadía que enseñar a escribir académicamente era tarea de los profesores. Con una buena formación académica, los hablantes/escritores somos capaces de movernos entre distintos registros y estilos. Si alguien escribe sus ensayos de clase con la escritura que usa en los mensajes, es trabajo del maestro enseñarle la ortografía (y otras cosas) adecuada para un ensayo. Y después puede regresar a sus mensajes de texto y escribirlos con abreviaciones y sin mayúsculas. Por último, una de las razones que daba la autora del video para promover la buena ortografía es: La mala ortografía no nos permite leer bien Esto es algo que muchos maestros dicen. Pero no es cierto. Generalmente, los errores ortográficos responden a una lógica interna, que el lector comparte y comprende. Es cierto que ejemplos que circulan en internet como “mi papa tiene 40 anos” pueden ser chistosos, pero a menos que el lector solo tenga intención de avergonzar al que lo escribió o hacer un chiste, no va a pensar de verdad que está diciendo “my dad has 40 anuses”. En conclusión, creo que es importante que tengamos una actitud positiva y amable hacia las personas que cometen errores de ortografía—especialmente si son nuestros estudiantes. Cuando uno no tiene problemas de ortografía, esta parece muy fácil. Las palabras con errores ortográficos chocan con la imagen mental que tenemos de la palabra y nos producen malestar. Y nos parece increíble que otras personas no lo sientan. Pero nos resulta muy difícil ver esas palabras de la misma manera que las ven las personas que no desarrollaron su ortografía de forma completa y fuerte cuando eran niños. Pero, por lo menos, consideremos la posibilidad de que no sean ni perezosos, ni “horrorosos”, ni objeto de burla. Así que dejemos de burlarnos de ellos (o de sus errores) y de avergonzarlos.

*********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.  Are you thinking I am going to talk about the way students "make up words" with their spellings? Well, I am not. First, because I do not believe students make up words when they make spelling errors, but they are really trying to spell real ones. What I want to talk about is made-up words that are made up... by teachers, known as pseudo-words. Pseudo-words are made-up words that look like real words in a certain language. Pseudo-words in English could be brike, loke, fiper, or dight. They do not exist as words in English, but they are pronounceable and follow patterns found in real English words, such as bride, poke, fiber, and light. Pseudo-words like blaya, rila, pacar, or puelo are nonexistent but possible words in Spanish (similar to playa, pila, rima, picar, and suelo). Pseudo-words have a space in the language classroom. Let’s see one example today. Let’s say you want students to learn the writing of the GUE, GUI sequences, vs. the writing of GE, GI. If you only use examples like “guerra” and “gente,” it is very likely students will read and spell those words right, giving the impression that they are perfectly aware of the contrast ge/gue. However, they will read and write them right because they already know those words. When students read them, they do not need to pay attention to the exact sequence of letters, because they simply recognize the words. And when students write them, they will probably spell them right because they have seen them before. However, when they need to write less familiar words, they will make errors like llege, lleguo, … If we want students to pay attention to the orthographic contrast (GE - GUE) so that this orthographic sequence is applied to ALL words (familiar, infrequent, and new words), you can use pseudo-words. For example, students can be asked to read these words: guelo - laguifa - gipar – lugueto – piguenar – pegifante – pogé Because students have never heard those words before, they cannot use the “recognition strategy,” that is, recognize the word and just say it as they know it is pronounced. They really need to pay attention to that orthographic pattern. You can also use these pseudo-words in dictation: you read them and students write them. I would add two more benefits of using pseudo-words in the class, in addition to the main benefit of directing students' attention to the specific orthographic aspect: 1) It is fun! Working with made-up words adds a playful element to the lesson. 2) It helps lessen the fear to unknown words. The presence of an unknown word in a sentence creates an uncomfortable feeling to some students, which makes them sort of freeze and not be able to understand anything else in the sentence. The first time I work with pseudo-words in a classroom, some students laugh nervously. But working with these made-up words helps those students to get used to encountering unknown words. (With the idea that when those unknown words are real, their lack of fear will allow them to work on context clues and vocabulary-increasing activities). Now, although the use of pseudo-words has its benefits in the classroom, it should be limited, and applied only on specific occasions with a specific purpose. A very important component of spelling is visual memory. After reading and writing a word many times, for years, that word gets engraved in our memory, and we do not need to think about the rules to write it. Therefore, students should spend most of their time writing real words, which are the ones that should get engraved in the students’ mental visual dictionary. Likewise, there is nothing wrong with reading using a “recognition strategy”. This is what allows us to read fast and fluently, and to focus on comprehension of texts. Therefore, teachers should focus on increasing students’ vocabulary, through reading and talking about a variety of topics in a variety of genres, registers, and styles. In future posts I will give other ideas for using pseudo-words in the classroom… in a timely manner. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.  There is no way to avoid the issue of the stress marks (acentos) when talking about spelling in courses of Spanish for Heritage Language Learners. Many students and teachers will agree that this is one of the most difficult aspects of spelling to learn. And it is! In order to place the stress mark in the right place, the writer needs to:

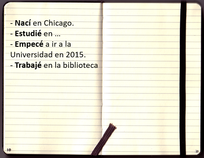

And ... do all this in the back of your head while you think of more important things, such as the ideas you want to express. And do so very quickly, because you need to move on to the next word. However, as many students, teachers, and researchers have noticed, the process stops at the second step, when students cannot identify the stressed syllable of the word. Dr. María Carreira, a professor of Spanish Linguistics at Cal State University Long Beach, explained that the problem is not that the students lack the ability to perceive stress, but rather that they seem unable to access this implicit perception and turn it into an explicit identification. It makes sense. If the student didn't know (implicitly) what the stressed syllable was, they would not pronounce the word right. And that's not the case. Dr. Carreira trained the students into improving their ability to locate the stressed syllable of a word, by making them listen recordings of words in which the stressed syllable was read with an amplified pitch, length, and loudness. Dr. Sara Beaudrie, another professor and researcher I have mentioned before in this blog, also conducted a study in which she trained students to identify the syllable before the rules where introduced. I want to suggest here an alternative (or, rather, complementary) manner to address stress marks in the classroom: study groups of words that are related and that follow the same pattern. For example, the past tense (preterit) for yo and él / ella: such as: nací, crecí, vivió, nació, creció, vivió, empezó, estudió, etc. (Regular verbs only). Students, by themselves or in groups, can write autobiographies or someone else’s biography, and work with those forms. Other groups of words that share a stress pattern while sharing some communicative functions are:

Working on each of these groups has the following benefits:

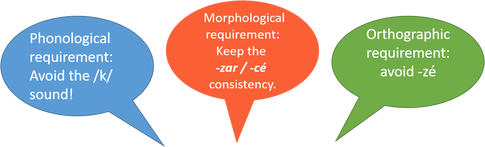

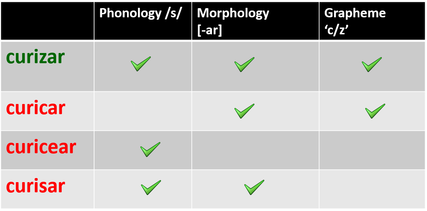

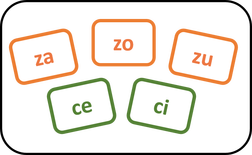

That said, identifying the stressed syllable, learning the rules, and even grouping words into patterns, will not be enough. Adding the stress mark to a word has to become automatized enough so that the student can do it while focusing on something else. As with many other aspects of language, we need to distinguish between competence and performance. While a student might know where and where to write the accents (competence), they might not do it every time they write something (performance). As tempting as it might be to repeat the rules over and over, students should be given the opportunity to practice placing the stress marks so that it becomes an automatic task that does not require any thinking. References: Beaudrie, S (2017). The Teaching and Learning of Spelling in the Spanish Heritage Language Classroom: Mastering Written Accent Marks. Hispania, 100, 4. Carreira, M. (2002). When phonological limitations compromise literacy: A connectionist approach to enhancing the phonological competence of heritage language speakers of Spanish. In S. Hammadou (Ed.), Literacy and the second language learner. Greenwich, CT: IAP. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment.  In a previous post, I mentioned that spelling rules have a limited role in the development of spelling. One of the reasons for that limited role is the fact that our mind does not have the time to stop and recall a specific rule during real time writing. Instead, our mind relies more strongly in the visual memory of the word. After repeated exposure to a written word, as well as after repeatedly writing that word for years, the visual image of that written word is engraved in our mind. This allows us to read and write more quickly and confidently. And it’s that stored image of a word that allows us to reject a misspelled word with a feeling that “it looks bad”.  However, students keep asking for rules … and then forgetting them. There is nothing wrong with forgetting a rule, but only if the image of that word is strongly engraved in the mind so that the rule is not really needed. In a workshop for prospective teachers (heritage language themselves), I asked the students: “Why do you think spelling is so difficult?” And a few responded: “Because students are lazy and don’t study the rules”. Then, I proceeded to explain a very simple spelling rule: when you have to choose between Z and C, Z is used before A, O, U; and C is used before E and I. And I gave a few examples. Students told me they understood the rule--and most of them were familiar with it already. Immediately after that, I gave them a dictation of words, and I told them that none of them were spelled with S, only Z or C. Among those words were: cine, cena, zapato, cereza, hice, realicé and cero. Can you guess which ones many of them got wrong? Yes, they were realicé and cero. More than half of the class wrote zero, and more than one third wrote realizé. There were no errors in any of the other words, despite the fact that they followed the same rule. Students were obviously swayed by the visual image of zero and realize in English. When I showed students why those spellings were wrong, according to that simple rule they had just learned, a few still “complained” that cero and realicé looked wrong. Students were not lazy, or forgetful; the memory of the image of zero and realize simply had a greater weight. This is not so strange. When we see a friend on the street, we recognize his or her face because we have a stored memory of it, not because we “know” some facts about that friend’s face. When we see a red light it just feels right to stop; we do not need to think about the rule: green > go; red > stop. For cases in which the spelling of a word goes against a strong image of a word, students will need negative instruction (that is, what NOT to write) and many opportunities to strongly engrave the image of that word in their minds. Here are some other words similar to cero and realicé: analicé, docena, cebra, bronce, utilicé, trapecio. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment. En esta entrada voy a comentar un error que una lectora de este blog sugirió en un comentario: cuidad por ciudad. Aunque no es uno de los errores más comunes, probablemente muchos maestros lo habrán encontrado en sus ensayos. De hecho, en el estudio de la Dra. Sara Beaudrie que ya mencioné anteriormente, se recoge este error, junto con otras inversiones de vocales, como teine por tiene, que incluso pueden cruzar el límite entre sílabas, como en gruadar por graduar. Creo que en estos errores entran en juego distintos factores, de los cuales voy a destacar estos dos: 1) Dificultades en la conciencia fonológica. La conciencia fonológica es la habilidad de identificar y segmentar los fonemas de una palabra. Esta habilidad se desarrolla en la infancia, mediante algunas actividades no escolares, como en canciones en las que se juegan con rimas (a, e, i, o u, burriquito como tú…), y más adelante en los primeros años de escolarización.  Esta es una habilidad necesaria para el desarrollo de la lecto-escritura, ya que la ortografía consiste en asignar letras a fonemas, pero, a su vez, el aprendizaje de la ortografía ayuda a identificar los fonemas de una palabra y a segmentar estas en cada una de sus unidades. Por ese motivo, nos parece que oímos mejor cada uno de los sonidos de una palabra cuando sabemos cómo se escribe. Hay estudios que sugieren que la conciencia fonológica es transferible, es decir, la conciencia fonológica que los estudiantes desarrollaron en inglés en sus clases de Kindergarten y primer grado se transfiere al español, con lo cual no tenemos que empezar de cero cuando los estudiantes toman su primera clase de español en la secundaria. Sin embargo, es muy posible que algunos estudiantes tengan algunas dificultades a nivel de conciencia fonológica en español, debido a que la conciencia fonológica tiene un efecto menor en la ortografía en inglés que el que tiene en español, y al hecho de que la conciencia fonológica desarrollada en la infancia disminuye con los años, cuando escribimos y leemos sin necesidad de fijarnos en cada letra. Las secuencias de vocales (ei, ie, iu, ou, …) son más difíciles de segmentar que las secuencias consonante-vocal (ma, te, po, li, ga). ¿Por qué? Porque la pronunciación de ciertas vocales es muy similar (e ≈ i, o ≈ u, i ≈ u, etc.) y al pronunciarlas consecutivamente las acercamos aún más, para facilitar la articulación (en un fenómeno llamado coarticulación), y porque las vocales en diptongo se pronuncian más rápidamente que las vocales entre consonantes. Por ese motivo, no es de extrañar que un estudiante con una conciencia fonológica no muy desarrollada en español tenga más dificultades en segmentar palabras con dos vocales consecutivas, lo cual da lugar a errores como cuidad (o suidad), teine, preferie o prefere, etc. En un estudio que realicé recientemente, esto es precisamente lo que observé. Los estudiantes tenían más dificultades con palabras que contenían vocales consecutivas en tareas como: escribir esas palabras a partir de un dictado, contar sus sílabas, y decir si habían oído una cierta sílaba (como pien) en una oración corta que habían escuchado. 2) Por otra parte, es muy posible que el error se deba a que el estudiante dicen "suidad", y que esa palabra forme parte de la variedad del español a la que está expuesto (o una de ellas). Por ejemplo, en el diccionario del español de Nuevo México y Colorado, de Rubén Cobos, se recogen palabras como: envitar, entriega, a escuras, espital for hospital, dijir, disierto, disconsuelo, dirigemos, dispensa, dispertar, nos divirtemos, divurcio, durmir, incontrar, imbicionar, empedido, empertinente, prencipal, prencipio, siñor, sirvir, sofrir y ... suidá (1). Y en una antología de cuentos en español de Colorado y Nuevo México, aparecen también palabras como envitado, rirse, incontrar, voltiar, pasiar, dicir, cairía, vían, nochi... y suidad (2). Si tenemos esto en cuenta, es muy posible que los estudiantes estén escribiendo ciertas palabras tal como las han oído y como las pronuncian. Mi sospecha es que la razón de muchos de los errores ortográficos que afectan a las vocales se encuentra en una confluencia de estos dos factores. Cobos, Rubén (2003) “A Dictionary of New Mexico and Southern Colorado Spanish” 2nd edition. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press. Rael, J.B. (1939). Cuentos Españoles de Colorado y de Nuevo Méjico (Primera Serie).The Journal of American Folklore, 52, 205/206, 227-323.  I am a strong believer that in order to help students to correct or avoid spelling errors, we need to understand why they make that particular error. It is not enough to say: “they should have written ‘c’ instead of ‘s’.” We need to understand why the student wrote ‘s’ instead of ‘c’ in that particular context. And, for that, we need to consider why we need to write ‘c’ and reject all the other options. In this post, I want to focus on one particular error. In a previous post, I explained that many spelling errors involving s/z/c were found in verbs ending in –zar, such as empezar, empecé, empezó, alcanzar, alcancé, alcanzamos, etc. And here I want to explain why these words are particularly problematic, as well as a little experiment that I did, and that you can do in your classroom. First, these words are particularly problematic because the sound /s/ is associated with three different letters: s, z, and c. Therefore, the student needs to choose between three options. Second, the different choices require different strategies. Let’s see… To write empezar, we need to write z and reject ... s (*empesar), because that’s how the word is spelled. There is no orthographic rule that allows us to know that. In fact, other verbs end with -sar: like pesar, pensar, besar, or pasar. That makes the word *empesar not so ugly at our eyes (or the students' eyes). c (*empecar), because that would result in the wrong pronunciation: like /empekar/. Now, to write empecé, we need to write c and reject ... s (empesé), because empecé is a conjugated form of of empezar, and not empesar. Z (empezé), because there is a rule that says that z appears only at the end of a word or before a, o, u, but not before e or i. Therefore, the reason why writing verbs ending in –zar is so difficult is that the student faces three conflicting requirements: In 2017, I conducted an experiment with Spanish HL students.* I gave them sentences with made up words similar to empezar, which they had to complete with a related made-up word. Try to complete the sentence before you look at the right answer. Ayer yo curicé mi pasaporte, pero tú todavía lo tienes que ______________. [scroll down to see the answer] The right answer is curizar. Did you come up with this word? A few students did, but many of them wrote the wrong word. What was interesting is that their wrong answers were either: curicar curicear curisar Each of these words is the result of breaking one of the demands for that word, as shown in this table. What does that experiment show us?

It shows us that writing verbs like alcanzar, empezar, … and their related forms is much more difficult that it might seem, because writing the right form requires paying attention to different (and conflicting) things. Most of us can do it because we have a strong visual memory of these written words. Doing this experiment with made-up words allows us to look at those words without having any visual memory of them. You can try this experiment with your students, as a spelling game, with the objective of forcing students to focus their attention to the morphological relations between words and the –zar > -cé alternation. Here are some sentences you could use:

*Llombart-Huesca, A. (2017). “Morphological Awareness and Heritage Language Learners.” Linguistics and Education, 37, 11-31. *********************** Have you encountered any interesting spelling error (frequent or not) you would like me to write about? Feel free to let me know in a comment. |

BLOG ON SPELLING

This is a blog about spelling in Spanish Heritage Language Learners. Some posts will be in Spanish and some in English. Feel free to ask your questions in the comments section.

Archives

September 2023

Popular Posts

Made-up words and other fipers. Tips for teaching stress marks. Los hablantes nativos y la ortografía |

||||||||||||